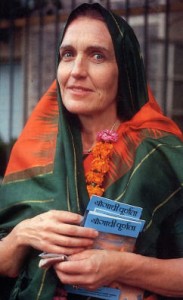

Three Days in Nicaragua by Lavangalatika Devi Dasi

In pre-glasnost days a veteran book distributor

finds a way to get Bhagavad-gita As It Is to the Russians.

After going through immigration at the Agosto de Sandino Aeropuerto at Managua. I stood in line to purchase $60 worth of cordovas (the local currency), which is required for anyone entering the city. Having been told, inaccurately, that everything is inexpensive in Nicaragua, I had brought only $200 in cash with me.

More important, I had two hundred copies of the Russian translation ofBhagavad-gita As It Is, by His Divine Grace A C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. I had come to give them to Russian officials and professionals stationed in Managua. At that time, the winter of 1985, it was easier and safer to distribute Srila Prabhupada's books to Russians outside the Soviet Union. The book had been newly published. I felt it was important to distribute as many copies as possible, because whenever Bhagavad-gita As It Is is translated into a new language, many new devotees j of Krsna are made.

In customs, a uniformed young lady confiscated my books. She said that customs would deliver them to the Russian embassy, but I insisted I would have to do it myself. Unfortunately, the administrator of customs had already gone home for the night, so she said I should come back the next day, as it would take that long for the books to go through the clearing house.

I took a cab and asked for the Hotel Central, the largest hotel near the airport and the only one I'd heard of. I had also been told that the rates were reasonable there. It was a very dark, humid night. The short ride on the bumpy, unlit road cost five hundred cordovas, more than $20. The hotel seemed to be empty, but they said they had no available rooms. It was just as well since the rooms cost $75 a night Obviously, I had come to the wrong place, so I took another taxi back down the dark, bumpy road that led to the city.

As I sat in the car, the surrounding darkness was suddenly fractured on all sides by explosions. It was not war but fireworks set of in celebration of the Fiesta de la Virgen de Nicaragua, a ten-day festival, my driver explained. In the yards of all the houses were little altars for the Virgin, with strings of lights and offerings of sweets, bananas, and flowers. People were visiting one another, and processions were being held. The scene reminded me of Diwali, the festival of lights in India.

I tried two more hotels, which were also full. and finally checked in at the Estrella Blana for $50 a night It was a new hotel, modern and clean, and in the lobby stood a statue of the Virgen de Nicaragua, smiling sweetly on an altar draped with red and green lights.

Finally, in my room after a long, hot day. I went to take a shower, but turning the faucet produced not a drop of water. The shower held only a tiny baby scorpion crawling on the tiles. When I called the front desk, they told me that on Tuesdays and Thursdays there was no water in Managua until 10:00 P.M. I'd have to wait two hours.

Next morning, while chanting on my beads. I heard outside my door."Zdra-sTuite." I could hardly believe it Russian!

I opened the door to find an elderly lady talking to a young man. I had one book that I had kept in my handbag, so I gave it to her. I told her it was book about Indian culture, including history and yoga, and that it was the favorite book of Mahatma Gandhi. She was delighted. We spoke briefly. She told me she was an engineer and that the American blockade of Nicaragua had made life very difficult there. If I accomplish nothing else while I'm here. I thought, delivering this one book makes this whole journey worthwhile.

I soon had to move to a cheaper hotel to conserve my money. Taking another taxi, I asked the driver where the downtown area was. He told me that in Managua there is none. With my limited Spanish. I learned that in 1972 a tierra moto, or earthquake, had destroyed everything, killing thousands of people. There had not been enough money to rebuild, and there was fear of building high-rise structures in the same place. Instead, clusters of low buildings appeared, a few of which were luxury developments.

Throughout the area, however, were stretches of wasteland covered with piles of rubble overgrown with grasses and junglelike vegetation. The surroundings were very disorienting. People stood in long queues for milk, meat, or buses, which were very infrequent There were also many open trucks carrying people on the pothole-filled road. A big sign by the road read, "Ne le falta a la Patria" "Don't let your country down."

The actual city center was a newly-built covered market with rows of stalls, some piled high with fruits, including bananas and enormous papayas. There were also shoe shops. The peasant vendors were mostly women with long black braids, jeweled earrings, and colorful clothing.

My next hotel was the ruin of a former mansion and was run by a Lebanese family that had settled there. The banisters were broken, the carpet and curtains were torn, the wallpaper had peeled off, the windowpanes were broken, and the ill-fitting doors and floorboards creaked. I seemed to be the only guest, but neither this fact nor the shabby appearance of the place were reflected in the price $35 a night. Still, I had to wait there until the next day, when I could try to get my books from the customs administrator.

I ate a papaya and later went for a walk. On one side was a residential neighborhood of well-kept houses and lawns mostly embassies. Young people in dark-green military uniforms could be seen about. In the other direction were empty lots overgrown with tropical grass. A friendly old lady spoke to me as I passed, commenting on the irregularity of the buses.

The nearby cafe had no milk, and two boys started to follow and tease me, so I returned to my run-down hotel room and locked myself in for the night

In the morning I went straight to the customs office to claim my books. A small group of people, also waiting to get their things out of customs, were making jokes about the inefficiency of the government It seemed that in general, people were not afraid to speak their minds under the Sandinista regime, and that the paranoia pervading the Eastern Bloc countries was absent.

After a short wait I was called to see the administrator. He was a young man, as most Sandinista officials seemed to be, and was very helpful. He signed the paper necessary for me to collect my books, and there was no red tape, no bribes, no corruption. I simply located my books in the customs shed and paid a small fee, equivalent to fifty cents, to the cashier.

I was then left with $50, some cordovas, and two hundred Bhagavad-gitas to distribute. I would have to distribute all of them that day, since I was to leave on the next First I went to the Russian embassy and handed a book to anyone I met on the grounds on my way to the building. The First Secretary appeared and put a stop to the initial rush of eager takers. He asked my name and why I was passing out the books. He said I should give the rest of the books to him and he would distribute them himself. I figured it was about time to leave.

I returned to the covered market and this time found several Russian shoppers, who gladly accepted books. The taxi driver helped me locate other Russian shoppers. Our operation attracted much attention the market vendors even wanted books, so I promised I would bring Spanish editions on my next visit Since I was giving the books away, my exchanges with these people produced a mutual feeling of good will. In the parking lot was a Volkswagen van that had brought the Russians. The driver was there, and a man was seated in the rear. Full of confidence. I approached them smiling, book in hand. But the man in the back shot forward, slamming the sliding door in my face and yelling "Bbi xodit" "Get out!"

We then drove a long way from town to a hotel where some Russian professors were staying. It was run by an American who had married a Nicaraguan girl. He had lived there for fifteen years. I left a small stack of books with the management for later distribution, as I couldn't get to see the professors.

On the way back to Managua at dusk, we gave a lift home to Jaime, one of the waiters from the hotel. He told us it normally took him four hours to go home by bus. He also complained about how it cost him the equivalent of $40 to buy a pair of pants. He lamented about how nice things used to be in the good old days before these "bastards" (Sandinistas) had ruined everything.

I was surprised to hear the last comment because in the "good old days," a few years before, the dictator Somoza used to feed his prisoners to his pet panthers. It seems people can never be satisfied. In the words of Srila Prabhupada, "The whole world is running after happiness, but there is none. The foolish animal will run after water in the desert where there is no water. The whole material civilization is like this. This is the place of suffering, and you are seeking after happiness."

Srila Prabhupada also said that people are transformed into thieves when they plan economic development for sense gratification, failing to recognize Krsna as the proprietor of everything. A ruler should be a representative of God, so that the people can automatically be blessed with all the material resources needed to support spiritual life.

After arriving back at the Estrella, I decided to distribute a bag of books to some Russian doctors who lived nearby. I stumbled in the dark along the uneven dirt path that connected their houses. A young couple invited me in to sit down and talk. In the same neighborhood, however, a heavily built woman stood at her door watching my every move, as if to say I had already gone too far.

That was my last night. Back at the hotel lobby. I sat and waited near the brightly lit statue of the Virgin of Nicaragua to see if any more Russians would walk by. A television was on in the lobby, and there was a movie about a birthday party in an American home. Children were singing "Happy Birthday," and the parents were smiling. Just as the little boy was blowing out the candles on the cake, masked gunmen suddenly burst in and shot everyone dead. Then I watched black people getting beaten up by the police, kids taking drugs, robberies, muggings, drunks one bizarre horror after another. Though it was obviously anti-American propaganda. I thought how, sadly, these scenes are in fact part of the documentary of life in the Western world.

Suddenly the TV stopped working. The picture tube had burned out.

I had thirty books left, which I had to take back to Costa Rica in my luggage. I also left some copies with the Russian woman I had met in the hotel to give to her friends.

On leaving Nicaragua. I was thinking what a good place it is to preach Krsna consciousness, because the people are very friendly, and they are inclined to religion and enjoy festivals. The people are poor but do not seem to be repressed by the Sandinista government. I managed to reach a few Russians, but here is a whole country waiting for the mercy of Lord Caitanya's sankirtana movement.

Source: http://backtogodhead.in/three-days-in-nicaragua-by-lavangalatika-devi-dasi/